Here are some more ideas to add to my myths about bipolar disorder:

Myth: Medications don’t work for me.

For some people this may be true, but we all need to give our meds a chance. Treatment guidelines anticipate initial failures, and while no two guidelines are in agreement they are all based on the premise that eventually you will find a medication or combination of medications that will help you

Myth: Lower quality of life and sluggish cognition are fair trade-offs for reducing mood symptoms.

False. In the initial phase of treatment, meds overkill may be justified to bring your illness under control. But full recovery is based on improving your overall health and ability to function, not just eliminating mood symptoms. Over time, the side effects of medication tend to go away, so patience is advised. You may choose to live with minor side effects such as mild hand tremors. But if major side effects persist, you should work with your psychiatrist in adjusting doses or switching to different meds. The onus is on you to alert your psychiatrist to major side effects and to insist he or she take appropriate action.

Myth: Once you’ve been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, you can forget about leading a normal life.

False. Living with bipolar disorder is a challenge, and you may have to change your expectations, but you should never give up on living a rewarding and productive life.

I hope this is helpful. This issue can be very complex.

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

Why Zombies Eat Brains

For some reason many of my clients have been obsessed with the subject of why zombies eat brains--at least the adolescents have been. And I guess they feel I would know the answer because I work with brains (note: I do not work physically with brains, that would be a neurosurgeon - perhaps one would get better information by consulting one of them.)

Much of my research focused on physical and psychological needs for zombies to eat brains, as well as habitat needs.

One study found that the undead have a significant reduction in the pineal gland. Perhaps Zombies are compensating for a lack of this significant area of the brain, and by eating brains they feel they will make up for the lack of theirs.

Brains are also very high in protein/nutrients.

Recent studies have shown that glial cells, which make up the bulk of a brain, have the ability to act as stem cells, at least as far as being able to replicate other brain cells. Zombies are probably going after the glial cells to help restore some of their brain function.

Brains are also rich in cholesterol, which is essential for maintaining cell membrane pliability, which is a particular problem at the low body temperatures typical of zombies in non-tropical climates.

Psychologically, the act of eating brains can ease the pain of being dead (see movie "From Beyond")This would actually make more sense, when one considers some studies which note that zombies probably don't eat for nourishment, and perhaps the act of brain-eating represents an unholy, instinctive attempt on the undead's part to regain their lost minds.

Also we need to consider that by being dead, many zombies are missing teeth, and prefer eating something that's easy on the gums.

One last idea is that zombies eat brains as a matter of managing their habitat. As is well-known, a zombie's bite will infect a normal human and turn him or her into another zombie within a matter of minutes or hours. This, of course, assumes that the attacking zombie or its pack do not completely consume the victim. Now, you figure that a solo zombie or even one or two attacking in conjunction cannot eat all of the meat parts of a given victim in one sitting. This means that if a zombie just eats an arm, pretty soon it will be joined by a one-armed zombie that is also now on the hunt. Therefore it must now compete with the nub zombies in the pursuit of tasty human flesh. Eating the brain is both satisfying and prevents the rise of new zombies, so the zombie population does not increase to unsustainable levels.

I hope this helps my clients in their obsession with the subject. For those who are my clients, please don't ask again.

Much of my research focused on physical and psychological needs for zombies to eat brains, as well as habitat needs.

One study found that the undead have a significant reduction in the pineal gland. Perhaps Zombies are compensating for a lack of this significant area of the brain, and by eating brains they feel they will make up for the lack of theirs.

Brains are also very high in protein/nutrients.

Recent studies have shown that glial cells, which make up the bulk of a brain, have the ability to act as stem cells, at least as far as being able to replicate other brain cells. Zombies are probably going after the glial cells to help restore some of their brain function.

Brains are also rich in cholesterol, which is essential for maintaining cell membrane pliability, which is a particular problem at the low body temperatures typical of zombies in non-tropical climates.

Psychologically, the act of eating brains can ease the pain of being dead (see movie "From Beyond")This would actually make more sense, when one considers some studies which note that zombies probably don't eat for nourishment, and perhaps the act of brain-eating represents an unholy, instinctive attempt on the undead's part to regain their lost minds.

Also we need to consider that by being dead, many zombies are missing teeth, and prefer eating something that's easy on the gums.

One last idea is that zombies eat brains as a matter of managing their habitat. As is well-known, a zombie's bite will infect a normal human and turn him or her into another zombie within a matter of minutes or hours. This, of course, assumes that the attacking zombie or its pack do not completely consume the victim. Now, you figure that a solo zombie or even one or two attacking in conjunction cannot eat all of the meat parts of a given victim in one sitting. This means that if a zombie just eats an arm, pretty soon it will be joined by a one-armed zombie that is also now on the hunt. Therefore it must now compete with the nub zombies in the pursuit of tasty human flesh. Eating the brain is both satisfying and prevents the rise of new zombies, so the zombie population does not increase to unsustainable levels.

I hope this helps my clients in their obsession with the subject. For those who are my clients, please don't ask again.

Monday, January 25, 2010

Bipolar Disorder

I have given a lot of thought to bipolar disorder over the last day, since I have been asked to blog on it. One thing that I have noticed about the disorder is that it is the new trendy diagnosis is psychiatry, along with Aspergers disorder. Ten years ago I noticed that ADHD also had its moment of fame. Many of my adult clients, who were children ten years ago were diagnosed with ADHD and it significantly and negatively altered their lives... Many of them didn't have ADHD, they were just boys! (See "Raising Cain", and excellent documentary on this phenomenon, PBS.com). I fear that in many ways a diagnosis of bipolar is following the same trend.

Maybe I should highlight my personal bias: I rarely diagnose people in my practice of psychotherapy. In many instances, I find diagnosing people with a disorder to be counterproductive, since many people will conform themselves to a diagnosis and become dependent on that diagnosis. For example, I had a client who was diagnosed by another practitioner to have borderline personality disorder. This client began to use this diagnosis as an excuse to avoid personal responsibility. I attempted to resolve the clients thinking errors of "I can't work anymore because of my severe problems with emotional regulation and distress intolerance". The client hadn't a problem working before the diagnosis, in fact, the client was a very successful accountant.

Anyways, back to bipolar. Although I feel clinicians should be rarely diagnose their clients, it is necessary, at times, to establish a good working treatment plan, but a clinician should focus on the treatment plan, not the diagnosis. When a client suffers from bipolar disorder, a good combination of medication and psychotherapy needs to be utilized. Oftentimes, someone suffering from this issue will only utilize one or the other, more often taking the medication route over the psychotherapy route. The combination needs to addressed, because a client who has bipolar often has a chaotic environment and disruptive interpersonal relational style.

I have also found, as with many other psychiatric disorders, bipolar is misunderstood. Although, I feel that it has recently been over-diagnosed, I also feel that many who truly have this disorder have minimized it. Here are some misconceptions:

1. Everyone has their ups and downs, so mine aren’t that serious.

Yes, everyone has good days and bad days, but when these ups and downs seriously interfere with your ability to work, relate to others and function effectively, it is advisable to seek out a psychiatrist.

2. Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder.

Half true. Bipolar disorder certainly affects mood, but it also affects cognition and the ability to perform mental tasks. Some days we can out-think Stephen Hawking. Other days we make Forrest Gump look like an intellectual.

3. Yes, but bipolar disorder is still a mood disorder.

Granted, but for most of us it is also part of a package deal that may include anxiety, substance and alcohol abuse and sleep disorders. Also, researchers are finding smoking guns linking the illness to heart disease, migraines and other physical ailments.

4. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood swings ranging from severely depressed to wildly manic.

Not necessarily. Most people with bipolar disorder are depressed far more often than they are manic. Often, the manias are so subtle that they are overlooked by both patient and psychiatrist, resulting in misdiagnosis. People with bipolar disorder can also enter long periods of remission.

5. Mania is like being on top of the world—if you could only put it in a bottle and sell it.

You wouldn’t want to with most manias. True, some forms of mild mania are characterized by feelings of elation, but other types have road rage features built in. More severe mania turns up the heat, resulting in different kinds of out-of-control behavior that can ruin your career, relationships and reputation.

6. Bipolar disorder is caused by a chemical imbalance of the brain.

This is the simpler explanation—what you tell your family and friends. What you need to know is our genes, biology and life experience make us extremely sensitive to stress. Various stressors, such as personal relationships and financial worries, have the potential to trigger a mood episode if not effectively nipped in the bud.

7. Medications are all you need to combat bipolar disorder.

False. While medications are the foundation of treatment for bipolar disorder, recovery is problematic without a good lifestyle regimen (diet, exercise and sleep), effective coping skills and a support network. People with bipolar disorder also benefit from various forms of talking therapy and religious/spiritual practice.

I will make more comments on this in a future post... I've got to get some sleep!

Maybe I should highlight my personal bias: I rarely diagnose people in my practice of psychotherapy. In many instances, I find diagnosing people with a disorder to be counterproductive, since many people will conform themselves to a diagnosis and become dependent on that diagnosis. For example, I had a client who was diagnosed by another practitioner to have borderline personality disorder. This client began to use this diagnosis as an excuse to avoid personal responsibility. I attempted to resolve the clients thinking errors of "I can't work anymore because of my severe problems with emotional regulation and distress intolerance". The client hadn't a problem working before the diagnosis, in fact, the client was a very successful accountant.

Anyways, back to bipolar. Although I feel clinicians should be rarely diagnose their clients, it is necessary, at times, to establish a good working treatment plan, but a clinician should focus on the treatment plan, not the diagnosis. When a client suffers from bipolar disorder, a good combination of medication and psychotherapy needs to be utilized. Oftentimes, someone suffering from this issue will only utilize one or the other, more often taking the medication route over the psychotherapy route. The combination needs to addressed, because a client who has bipolar often has a chaotic environment and disruptive interpersonal relational style.

I have also found, as with many other psychiatric disorders, bipolar is misunderstood. Although, I feel that it has recently been over-diagnosed, I also feel that many who truly have this disorder have minimized it. Here are some misconceptions:

1. Everyone has their ups and downs, so mine aren’t that serious.

Yes, everyone has good days and bad days, but when these ups and downs seriously interfere with your ability to work, relate to others and function effectively, it is advisable to seek out a psychiatrist.

2. Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder.

Half true. Bipolar disorder certainly affects mood, but it also affects cognition and the ability to perform mental tasks. Some days we can out-think Stephen Hawking. Other days we make Forrest Gump look like an intellectual.

3. Yes, but bipolar disorder is still a mood disorder.

Granted, but for most of us it is also part of a package deal that may include anxiety, substance and alcohol abuse and sleep disorders. Also, researchers are finding smoking guns linking the illness to heart disease, migraines and other physical ailments.

4. Bipolar disorder is characterized by mood swings ranging from severely depressed to wildly manic.

Not necessarily. Most people with bipolar disorder are depressed far more often than they are manic. Often, the manias are so subtle that they are overlooked by both patient and psychiatrist, resulting in misdiagnosis. People with bipolar disorder can also enter long periods of remission.

5. Mania is like being on top of the world—if you could only put it in a bottle and sell it.

You wouldn’t want to with most manias. True, some forms of mild mania are characterized by feelings of elation, but other types have road rage features built in. More severe mania turns up the heat, resulting in different kinds of out-of-control behavior that can ruin your career, relationships and reputation.

6. Bipolar disorder is caused by a chemical imbalance of the brain.

This is the simpler explanation—what you tell your family and friends. What you need to know is our genes, biology and life experience make us extremely sensitive to stress. Various stressors, such as personal relationships and financial worries, have the potential to trigger a mood episode if not effectively nipped in the bud.

7. Medications are all you need to combat bipolar disorder.

False. While medications are the foundation of treatment for bipolar disorder, recovery is problematic without a good lifestyle regimen (diet, exercise and sleep), effective coping skills and a support network. People with bipolar disorder also benefit from various forms of talking therapy and religious/spiritual practice.

I will make more comments on this in a future post... I've got to get some sleep!

Friday, January 22, 2010

Random Links

- National Geographic has a wonderful interactive map of Manhattan where you can make direct comparisons with before and after the city was developed.

- In South Africa, pigeons are faster than the internet.

- Its not the appendix's fault for being useless, its our modern world.

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Here are some random Maps

George Orwell, in his essay Why I Write, says of the aesthetic desire to write that "above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations".

Then there is the redesigned Tokyo map. I've bought a poster of this from Zero Per Zero.

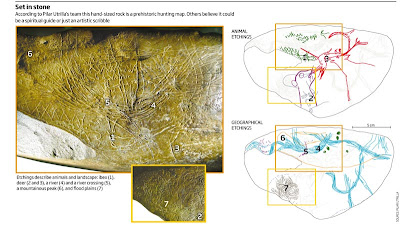

Scientists have also recently found what may be the oldest known map. Check out the overlay of animal drawings.

Finally, from the always reliably interesting Strange Maps, we have a reversed view of Europe.

Finally, from the always reliably interesting Strange Maps, we have a reversed view of Europe.

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Accountability

The majority of people I see in therapy are there because they do not want to make a decision—they want me (their therapist) to make a decision for them. When I think of almost every mental or relational problem I have helped people with, there inevitably is a responsibility issue at the core of the matter. This is what the defense mechanisms of projections, displacement, splitting (triangulation), and others are defending against—personal accountability!

The following is a list of defense mechanisms(notice how many of them deal with responsibility avoidance at an unconscious, preconscious and conscious level):

Level 1 Defence Mechanisms

The mechanisms on this level, when predominating, almost always are severely pathological. These three defences, in conjunction, permit one to effectively rearrange external reality and eliminate the need to cope with reality. The pathological users of these mechanisms frequently appear crazy or insane to others. These are the "psychotic" defences, common in overt psychosis. However, they are found in dreams and throughout childhood as healthy mechanisms.

They include:

· Denial: Refusal to accept external reality because it is too threatening; arguing against an anxiety-provoking stimuli by stating it doesn't exist; resolution of emotional conflict and reduce anxiety by refusing to perceive or consciously acknowledge the more unpleasant aspects of external reality.

· Distortion: A gross reshaping of external reality to meet internal needs.

· Delusional Projection: Grossly frank delusions about external reality, usually of a persecutory nature.

Level 2 Defence Mechanisms

These mechanisms are often present in adults and more commonly present in adolescence. These mechanisms lessen distress and anxiety provoked by threatening people or by uncomfortable reality. People who excessively use such defences are seen as socially undesirable in that they are immature, difficult to deal with and seriously out of touch with reality. These are the so-called "immature" defences and overuse almost always lead to serious problems in a person's ability to cope effectively. These defences are often seen in severe depression and personality disorders. In adolescence, the occurrence of all of these defences is normal.

These include:

· Fantasy: Tendency to retreat into fantasy in order to resolve inner and outer conflicts.

· Projection: Projection is a primitive form of paranoia. Projection also reduces anxiety by allowing the expression of the undesirable impulses or desires without becoming consciously aware of them; attributing one's own unacknowledged unacceptable/unwanted thoughts and emotions to another; includes severe prejudice, severe jealousy, hypervigilance to external danger, and "injustice collecting.” It is shifting one's unacceptable thoughts, feelings and impulses within oneself onto someone else, such that those same thoughts, feelings, beliefs and motivations as perceived as being possessed by the other.

· Hypochondriasis (a.k.a. somatization): The transformation of negative feelings towards others into negative feelings toward self, pain, illness and anxiety.

· Passive aggression: Aggression towards others expressed indirectly or passively.

· Acting out: Direct expression of an unconscious wish or impulse without conscious awareness of the emotion that drives that expressive behavior.

Level 3 Defence Mechanisms

These mechanisms are considered neurotic, but fairly common in adults. Such defences have short-term advantages in coping, but can often cause long-term problems in relationships, work and in enjoying life when used as one's primary style of coping with the world.

These include:

· Displacement: Defence mechanism that shifts sexual or aggressive impulses to a more acceptable or less threatening target; redirecting emotion to a safer outlet; separation of emotion from its real object and redirection of the intense emotion toward someone or something that is less offensive or threatening in order to avoid dealing directly with what is frightening or threatening.

· Dissociation: Temporary drastic modification of one's personal identity or character to avoid emotional distress; separation or postponement of a feeling that normally would accompany a situation or thought.

· Intellectualization: A form of isolation; concentrating on the intellectual components of a situation so as to distance oneself from the associated anxiety-provoking emotions; separation of emotion from ideas; thinking about wishes in formal, affectively bland terms and not acting on them; avoiding unacceptable emotions by focusing on the intellectual aspects.

· Reaction Formation: Converting unconscious wishes or impulses that are perceived to be dangerous into their opposites; behavior that is completely the opposite of what one really wants or feels; taking the opposite belief because the true belief causes anxiety. This defence can work effectively for coping in the short term, but will eventually break down.

· Repression: Process of pulling thoughts into the unconscious and preventing painful or dangerous thoughts from entering consciousness; seemingly unexplainable naiveté, memory lapse or lack of awareness of one's own situation and condition; the emotion is conscious, but the idea behind it is absent.

Level 4 Defence Mechanisms

These are commonly found among emotionally healthy adults and are considered the most mature, even though many have their origins in the immature level. However, these have been adapted through the years so as to optimize success in life and relationships. The use of these defences enhances user pleasure and feelings of mastery. These defences help the users to integrate conflicting emotions and thoughts while still remaining effective. Persons who use these mechanisms are viewed as having virtues.

These include:

· Altruism: Constructive service to others that brings pleasure and personal satisfaction.

· Anticipation: Realistic planning for future discomfort.

· Humour: Overt expression of ideas and feelings (especially those that are unpleasant to focus on or too terrible to talk about) that gives pleasure to others. Humour enables someone to call a spade a spade, while "wit" is a form of displacement (see above under Category 3).

· Identification: The unconscious modelling of one's self upon another person's character and behavior.

· Introjection: Identifying with some idea or object so deeply that it becomes a part of that person.

· Sublimation: Transformation of negative emotions or instincts into positive actions, behavior, or emotion.

· Suppression: The conscious process of pushing thoughts into the preconscious; the conscious decision to delay paying attention to an emotion or need in order to cope with the present reality; able to later access uncomfortable or distressing emotions and accept them.

Defense mechanisms protect us from being consciously aware of a thought or feeling which we cannot tolerate. The defense only allows the unconscious thought or feeling to be expressed indirectly in a disguised form. When these defenses become dysfunctional, dangerous, deviant or distressing, a person needs to seek treatment; however, it is essential to know that many of these defenses operate within all of us. These defenses are not inherently negative, some may be quite positive, like sublimation. However and indeed, many of these defenses can contribute to responsibility avoidance. For example, I once worked with an individual who was in extreme denial surrounding his extreme heroin addiction. He had convinced himself that it was natural and even healthy for him. He felt that everyone was out to get him and as long as he could maintain his job and his relationships, there was no reason to change. In a therapy group for substance abuse, many of the group members tried to “break him.” They would challenge and confront him until they were blue in the face (literally). However, none of their efforts worked. Yet one day he presented the group with a very depressed affect which was unlike his usual bravado. He stated, “My girlfriend left me and I think I am going to get fired, all because of my drug use.” Now, the defenses were down and the group could get some real work done. He was now ready, willing and somewhat able to grow out of this dysfunction… so we thought. As the group gave him suggestions, and praised him on “seeing through the pink haze,” he began to become a little bit stoic. He then began to follow the group’s lead by asking for advice, which they in turn were eager to give. Over the next week, he practiced the behaviors that the group told him to do, began a 12-step program as they had advised, and he attempted to be as honest as he could with others, also as the group had advised. During the next group, he was absent, and he never returned. “What happened… he was doing so well?,” group members asked. On a private phone call I had with him some weeks later, he told me that the 12-step group was full of “self-righteous do-gooders,” the people he attempted to be honest with rejected him, and all the advice the group had given him had “blown up in his face.” He has made the group accountable for his failed attempts of sobriety.

How do we evoke accountability within ourselves when we may be in a state of defensiveness? It has much to do with our relationships with others and how they respond to us. Good feedback from those who care does not include advice, this will only perpetuate responsibility avoidance. Good listening is key to evoke accountability.

Thomas Gordon described some roadblocks to listening:

• Asking questions

• Agreeing, approving, or praising

• Advising, suggesting, providing solutions

• Arguing, persuading with logic, lecturing

• Analyzing or interpreting

• Assuring, sympathizing, or consoling

• Ordering, directing, or commanding

• Warning, cautioning, or threatening

• Moralizing, telling what they “should” do

• Disagreeing, judging, criticizing, or blaming

• Shaming, ridiculing, or labeling

• Withdrawing, distracting, humoring, or changing the subject

“Why are they roadblocks?” Gordon continues:

“They get in the speaker’s way. In order to keep moving, the speaker has to go around them… They have the effect of blocking, stopping, diverting, or changing direction… They insert the listener’s ‘stuff’… They communicate: One-up role: `Listen to me! I’m the expert.’ And they put-down (subtle, or not-so-subtle).”

Certainly, it is a difficult, if not an impossible job to evoke accountability in others, and very often it is difficult to evoke accountability in ourselves. The first step is to realize that there are many aspects of our lives that we do not want to investigate. The second step is to become aware of the fact that we are responsible for those aspects; we are even responsible for things outside of ourselves. In a strange way, it can be liberating to know that we are responsible for everything in our environment—we are not to blame—but we are responsible.

The following is a list of defense mechanisms(notice how many of them deal with responsibility avoidance at an unconscious, preconscious and conscious level):

Level 1 Defence Mechanisms

The mechanisms on this level, when predominating, almost always are severely pathological. These three defences, in conjunction, permit one to effectively rearrange external reality and eliminate the need to cope with reality. The pathological users of these mechanisms frequently appear crazy or insane to others. These are the "psychotic" defences, common in overt psychosis. However, they are found in dreams and throughout childhood as healthy mechanisms.

They include:

· Denial: Refusal to accept external reality because it is too threatening; arguing against an anxiety-provoking stimuli by stating it doesn't exist; resolution of emotional conflict and reduce anxiety by refusing to perceive or consciously acknowledge the more unpleasant aspects of external reality.

· Distortion: A gross reshaping of external reality to meet internal needs.

· Delusional Projection: Grossly frank delusions about external reality, usually of a persecutory nature.

Level 2 Defence Mechanisms

These mechanisms are often present in adults and more commonly present in adolescence. These mechanisms lessen distress and anxiety provoked by threatening people or by uncomfortable reality. People who excessively use such defences are seen as socially undesirable in that they are immature, difficult to deal with and seriously out of touch with reality. These are the so-called "immature" defences and overuse almost always lead to serious problems in a person's ability to cope effectively. These defences are often seen in severe depression and personality disorders. In adolescence, the occurrence of all of these defences is normal.

These include:

· Fantasy: Tendency to retreat into fantasy in order to resolve inner and outer conflicts.

· Projection: Projection is a primitive form of paranoia. Projection also reduces anxiety by allowing the expression of the undesirable impulses or desires without becoming consciously aware of them; attributing one's own unacknowledged unacceptable/unwanted thoughts and emotions to another; includes severe prejudice, severe jealousy, hypervigilance to external danger, and "injustice collecting.” It is shifting one's unacceptable thoughts, feelings and impulses within oneself onto someone else, such that those same thoughts, feelings, beliefs and motivations as perceived as being possessed by the other.

· Hypochondriasis (a.k.a. somatization): The transformation of negative feelings towards others into negative feelings toward self, pain, illness and anxiety.

· Passive aggression: Aggression towards others expressed indirectly or passively.

· Acting out: Direct expression of an unconscious wish or impulse without conscious awareness of the emotion that drives that expressive behavior.

Level 3 Defence Mechanisms

These mechanisms are considered neurotic, but fairly common in adults. Such defences have short-term advantages in coping, but can often cause long-term problems in relationships, work and in enjoying life when used as one's primary style of coping with the world.

These include:

· Displacement: Defence mechanism that shifts sexual or aggressive impulses to a more acceptable or less threatening target; redirecting emotion to a safer outlet; separation of emotion from its real object and redirection of the intense emotion toward someone or something that is less offensive or threatening in order to avoid dealing directly with what is frightening or threatening.

· Dissociation: Temporary drastic modification of one's personal identity or character to avoid emotional distress; separation or postponement of a feeling that normally would accompany a situation or thought.

· Intellectualization: A form of isolation; concentrating on the intellectual components of a situation so as to distance oneself from the associated anxiety-provoking emotions; separation of emotion from ideas; thinking about wishes in formal, affectively bland terms and not acting on them; avoiding unacceptable emotions by focusing on the intellectual aspects.

· Reaction Formation: Converting unconscious wishes or impulses that are perceived to be dangerous into their opposites; behavior that is completely the opposite of what one really wants or feels; taking the opposite belief because the true belief causes anxiety. This defence can work effectively for coping in the short term, but will eventually break down.

· Repression: Process of pulling thoughts into the unconscious and preventing painful or dangerous thoughts from entering consciousness; seemingly unexplainable naiveté, memory lapse or lack of awareness of one's own situation and condition; the emotion is conscious, but the idea behind it is absent.

Level 4 Defence Mechanisms

These are commonly found among emotionally healthy adults and are considered the most mature, even though many have their origins in the immature level. However, these have been adapted through the years so as to optimize success in life and relationships. The use of these defences enhances user pleasure and feelings of mastery. These defences help the users to integrate conflicting emotions and thoughts while still remaining effective. Persons who use these mechanisms are viewed as having virtues.

These include:

· Altruism: Constructive service to others that brings pleasure and personal satisfaction.

· Anticipation: Realistic planning for future discomfort.

· Humour: Overt expression of ideas and feelings (especially those that are unpleasant to focus on or too terrible to talk about) that gives pleasure to others. Humour enables someone to call a spade a spade, while "wit" is a form of displacement (see above under Category 3).

· Identification: The unconscious modelling of one's self upon another person's character and behavior.

· Introjection: Identifying with some idea or object so deeply that it becomes a part of that person.

· Sublimation: Transformation of negative emotions or instincts into positive actions, behavior, or emotion.

· Suppression: The conscious process of pushing thoughts into the preconscious; the conscious decision to delay paying attention to an emotion or need in order to cope with the present reality; able to later access uncomfortable or distressing emotions and accept them.

Defense mechanisms protect us from being consciously aware of a thought or feeling which we cannot tolerate. The defense only allows the unconscious thought or feeling to be expressed indirectly in a disguised form. When these defenses become dysfunctional, dangerous, deviant or distressing, a person needs to seek treatment; however, it is essential to know that many of these defenses operate within all of us. These defenses are not inherently negative, some may be quite positive, like sublimation. However and indeed, many of these defenses can contribute to responsibility avoidance. For example, I once worked with an individual who was in extreme denial surrounding his extreme heroin addiction. He had convinced himself that it was natural and even healthy for him. He felt that everyone was out to get him and as long as he could maintain his job and his relationships, there was no reason to change. In a therapy group for substance abuse, many of the group members tried to “break him.” They would challenge and confront him until they were blue in the face (literally). However, none of their efforts worked. Yet one day he presented the group with a very depressed affect which was unlike his usual bravado. He stated, “My girlfriend left me and I think I am going to get fired, all because of my drug use.” Now, the defenses were down and the group could get some real work done. He was now ready, willing and somewhat able to grow out of this dysfunction… so we thought. As the group gave him suggestions, and praised him on “seeing through the pink haze,” he began to become a little bit stoic. He then began to follow the group’s lead by asking for advice, which they in turn were eager to give. Over the next week, he practiced the behaviors that the group told him to do, began a 12-step program as they had advised, and he attempted to be as honest as he could with others, also as the group had advised. During the next group, he was absent, and he never returned. “What happened… he was doing so well?,” group members asked. On a private phone call I had with him some weeks later, he told me that the 12-step group was full of “self-righteous do-gooders,” the people he attempted to be honest with rejected him, and all the advice the group had given him had “blown up in his face.” He has made the group accountable for his failed attempts of sobriety.

How do we evoke accountability within ourselves when we may be in a state of defensiveness? It has much to do with our relationships with others and how they respond to us. Good feedback from those who care does not include advice, this will only perpetuate responsibility avoidance. Good listening is key to evoke accountability.

Thomas Gordon described some roadblocks to listening:

• Asking questions

• Agreeing, approving, or praising

• Advising, suggesting, providing solutions

• Arguing, persuading with logic, lecturing

• Analyzing or interpreting

• Assuring, sympathizing, or consoling

• Ordering, directing, or commanding

• Warning, cautioning, or threatening

• Moralizing, telling what they “should” do

• Disagreeing, judging, criticizing, or blaming

• Shaming, ridiculing, or labeling

• Withdrawing, distracting, humoring, or changing the subject

“Why are they roadblocks?” Gordon continues:

“They get in the speaker’s way. In order to keep moving, the speaker has to go around them… They have the effect of blocking, stopping, diverting, or changing direction… They insert the listener’s ‘stuff’… They communicate: One-up role: `Listen to me! I’m the expert.’ And they put-down (subtle, or not-so-subtle).”

Certainly, it is a difficult, if not an impossible job to evoke accountability in others, and very often it is difficult to evoke accountability in ourselves. The first step is to realize that there are many aspects of our lives that we do not want to investigate. The second step is to become aware of the fact that we are responsible for those aspects; we are even responsible for things outside of ourselves. In a strange way, it can be liberating to know that we are responsible for everything in our environment—we are not to blame—but we are responsible.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)